African Forest Elephants

Critically Endangered

The African Forest Elephant is the smallest of the three living elephant species, and is native to the humid tropical forests in West Africa and the Congo Basin. In fact it only became its own species in 2021. Before that all African elephants were considered to be the same species: Loxodonta africana. It was only in 2021 that the taxonomy was finally changed to match what scientists had long argued: that the forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis, is its own species, separate from the African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana). That same year African elephants were downgraded from Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List to Endangered for the African savanna elephant and Critically Endangered for the newly split African forest elephant.

The Mega-gardener of the Forest

Forest elephants are smaller than their savannah cousins and have straighter, downward-pointing tusks, which are thinner and harder than the tusks of the savannah elephants and are used to push through the dense undergrowth of their habitat. They have smoother skin, in contrast to the moisture collecting wrinkled skin of savannah elephants. They also have rounder ears, from which they derive their Latin name cyclotis. Bulls of the species reach a shoulder height of 2.4–3.0 m. Females are smaller at about 1.8–2.4 m tall at the shoulder.

Photo by dsg-photo.com – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

African forest elephants, like their savannah and Asian cousins, can live for up to 65 years and are considered ‘gardeners of the forest’. Forest elephants need to eat a huge amount of vegetation to extract the nutrients required to power the biological machine that is an elephant’s massive body, meaning that they are capable of changing the vegetation structure of a forest.

The dung produced is also an incredible fertilizer, and the seeds of fruits or acacia pods pass through the elephant undigested, dispersing plant species and regenerating the forest. They are highly social and live in family groups of up to 20 comprised of adult cows, their daughters and subadult sons. Family members look after calves together, called allomothering.

Once young bulls reach sexual maturity, they separate from the family group and form loose bachelor groups for a few days, but usually stay alone. Adult bulls associate with family groups only during the mating season. Family groups travel about 7.8 km per day and move in a home range of up to 2,000 km 2 , moving according to the availability of ripe fruits in the forest. Their complex network of permanent trails pass through stands of fruit trees and connect forest clearings with mineral licks, and are reused by humans and other animals.

Group of African forest elephants digging at a mineral lick.

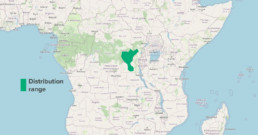

African Forest Elephants once occurred across the entire humid forest area of western and central Africa bu their range is decreasing and is highly fragmented in western Africa where seven range countries are reported to have fewer than a hundred each. The majority of the remaining population is found in six central African countries where they occupy an estimated 25% of their former range.

A dire situation

Compared to savanna elephants, the forest elephant is in much more serious danger of becoming extinct. Both African elephant species are threatened primarily by habitat loss and habitat fragmentation following conversion of forests for plantations of non-timber crops, livestock farming, and building urban and industrial areas. As a result, human-elephant conflict has increased. Poaching for ivory and bushmeat is a significant threat in Central Africa. The forest elephant population has declined by approximately 95% in the past 100 years due to the advent of modern firearms.

Around 50% of all surviving forest elephants are now in Gabon, despite Gabon only covering 13% of the total forest area of the region. Around 95% of the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the largest countries in Africa and the epicentre of Africa’s tropical rainforest eco-system, is likely to be almost empty of elephants.

Jaguar

Acknowledged as a terrestrial icon, the jaguar, with its majestic presence and distinctive behaviors, serves as a key player in maintaining ecological harmony. This species, recognized for its prowess as a top predator, plays a crucial role in regulating the populations of various prey species. The jaguar’s predatory influence creates a ripple effect throughout the ecosystem, shaping the distribution and behavior of other wildlife and contributing to overall biodiversity.

Near Threatened

The Jaguar is the largest cat species in the Americas and the third largest in the world after lions and tigers. It is currently classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN, having lost 20-25% of its population over the last 3 generations (21 years). It is threatened by habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, poaching for trade with its body parts and killings in human–wildlife conflict situations, particularly with ranchers in Central and South America. It has featured prominently in the mythology of indigenous peoples of the Americas, including those of the Aztec and Maya civilizations and is considered a symbol of strength and power. Although it is a dangerous predator with jaws that can pierce a turtle’s carapace or a mammal’s skull, humans are rarely attacked. According to Charles Darwin, the indigenous peoples of South America stated that people did not need to fear the jaguar as long as capybaras were abundant.

King of the Jungle

The Jaguar’s coat is covered in black spots and rosettes whose patterns serve as camouflage in areas with dense vegetation and patchy shadows. Jaguars living in forests are often darker and considerably smaller than those living in open areas, possibly due to the smaller numbers of large, herbivorous prey in forest areas. It stands 57 to 81 cm tall at the shoulders but its size and weight vary considerably depending on sex and region, with the size increasing from northern to southern populations. There is a rarer black morph, or melanistic jaguar, known as a black panther that is more common in tropical rainforest.

The Jaguar is generally most active at night and during twilight, although in densely forested regions of the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal they are active in daytime to coincide with the activity of their main prey species. They are good swimmers and play and hunt in the water. They attack from cover and usually from a target’s blind spot with a quick pounce that may include leaping into water after prey, as a jaguar is quite capable of carrying a large kill while swimming. They are strong enough to haul carcasses as large as a heifer up a tree to avoid flood levels. Jaguars are generally solitary except for females with cubs, and use scrape marks, urine and feces to mark their territory.

The Jaguar historically ranged from the southwestern US through the Amazon basin to the Rio Negro in Argentina with its stronghold the rainforest of the Amazon basin. However it has been

virtually eliminated from much of the drier northern parts of its range as well as northern Brazil, the pampas scrub grasslands of Argentina and throughout Uruguay.

Giant Otter

Endangered

Vocal giant

The Giant Otter or Giant River Otter is a South American carnivorous mammal. It is the longest member of the weasel family, Mustelidae, a globally successful group of predators.

Giant Otters are up to 1.7 m long, with a long well-muscled tail. It is well adapted to life in the water having short, extremely dense fur that keeps water from penetrating to the skin. Its velvety texture has made it highly sought after by fur traders. It has sensitive whiskers which allow it to detect changes in water pressure and currents, helping it to track prey. Its legs are short and stubby and end in large, webbed feet tipped with sharp claws, and it can close its ears and nose while underwater.

The Giant Otter is a social species, with family groups typically supporting three to eight members. The groups are centered on a dominant breeding pair and are extremely cohesive and cooperative. Although generally peaceful, the species is territorial, and aggression has been observed between groups. The giant otter is diurnal, being active exclusively during daylight hours. It is the noisiest otter species, and distinct vocalizations have been documented that indicate alarm, aggression, and reassurance. The giant otter subsists almost exclusively on a diet of fish, but may also eat crabs, turtles, snakes, and small caimans. It has no serious natural predators other than humans.

Giant Otters build dens, which are holes dug into riverbanks, usually with multiple entrances and multiple chambers inside. They give birth within these dens during the dry season. This makes it easier for the adults to catch enough fish for the growing young, and for the pups to learn how to catch fish. The entire group, including nonreproductive adults, which are usually older siblings to that year’s pups, collaborates to catch enough fish for the young.

The Giant Otter prefers freshwater rivers and streams, which are usually seasonally flooded, and may also take to freshwater lakes and springs. It constructs extensive campsites close to feeding areas, clearing large amounts of vegetation. It is endemic to South America and is distributed east of the Andes in the Orinoco, Amazonas, and Parana basins, and the hydrographic networks of the Guianas.

Back from the brink

The animal faces a variety of critical threats. Poaching has long been a problem and the species was so thoroughly decimated in the Brazilian Amazon that by 1971 there were only 12 left. Poaching restrictions has helped the population recover. More recently, habitat destruction and degradation have become the principal dangers, and a further reduction of 50% is expected in giant otter numbers within the 25 years after 2020 (about the span of three generations of giant otters). Typically, loggers first move into rainforest, clearing the vegetation along riverbanks. Farmers follow, creating depleted soil and disrupted habitats. As human activity expands, giant otter home ranges become increasingly isolated. Other threats to the giant otter include conflict with fishermen, who often view the species as a nuisance.

Multiple ICF projects across South America contribute to the preservation of the Giant Otter.

Hyacinth Macaw

Vulnerable

The Hyacinth Macaw is the world’s largest macaw species, and it is made even more magnificent by its deep cobalt blue plumage, large black beak and striking yellow facial highlights. Like many macaw species, it has disappeared from much of its range at the hands of the illegal pet trade. Now with a shrinking breeding range, some still enjoy refuge where the East Amazonian rainforest and drier palm savanna meet on the Xingu River in the heart of Kayapo territory. Like many macaws it is dependent on a few distinct types of palm fruit, which its massive bill is adapted to opening. However, the sloppy eating by macaws aids in seed dispersal of 18 species of plants and trees and thus planting new sources of food for themselves, often far from where the fruit was plucked.

Blue Majesty

The Hyacinth Macaw is enormous with its 100cm (40 in) length and wingspan, and body weight of 1.5 kg (3.5 pounds). The entire bird is bright, cobalt blue, with showy yellow eye-rings and a strip of yellow at the base of its lower mandible. Equally impressive are it very loud croaking and screeching calls.

Hyacinth Macaws pair for life and the mates are in constant physical and vocal contact. To nest they must find a natural cavity in a tree, and because of their great size the tree must also be immense. With large trees targeted by loggers, it is no surprise that this is another factor in their declines. Unlike many nesting bird’s chicks, capable of flight in 2 to 3 weeks, this macaw’s young needs a steady diet rich in protein (palm nuts) for over 3 months before they have matured enough to fledge and leave the nest.

Unlike many macaws that dwell in rainforest habitats, the Hyacinth Macaw prefers large, flooded palm swamps with patches of gallery forest. The Pantanal of the southwestern Brazil is comprised of just that, and is the stronghold for this species.

Recognized as an avian marvel, this species contributes to the pollination of native flora and plays a vital part in maintaining biodiversity. Its charismatic presence and distinctive behaviors make it an essential component of the intricate balance of its habitat.

Buff-Breasted Sandpiper

NEAR THREATENED

Long-distance voyager

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Calidris subruficollis) is a light buff-colored, diminutive shorebird that is unsuspicious of an approaching human. This may contribute to its steep decline over the past century, as well as the loss of the short grass habitats it favors. It is one of the longest distance migratory birds in North America, with one individual known to have flown 41,000 km round trip between its high Arctic nest site and its wintering site in southern South America.

At 18 cm in length and weighing only 60-70 gms the Buff-breasted Sandpiper is a relatively small inconspicuous, delicate, and slender sandpiper. Its small head is dove-like and it has yellow legs. Often they are seen alone or in small numbers and appear as a smaller, pale version of the Upland Sandpiper, which it often shares grassy habitats with.

The “Buffie’s” small size is compensated for on the breeding grounds where males gather into leks and perform elaborate displays with their wings held high, vertical aerial displays face-face-with other males. On the ground they battle each other using wings and feet, while females mildly stand by and await the victors. Buff-breasted Sandpiper leave the Arctic in late summer, travel a mid-continental route through the heartland of the US as well as an inland route in South America to the flooded Pampas grasslands of Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil.

Of all shorebirds, the Buff-breasted Sandpiper requires the shortest of grassland, and preferably with just the right amount of flooding. The species largely relies on grazed lands and sod farms during migration. They are mainly insect eaters.

Eastern Lowland Gorilla

⏺ Critically endangered

Grauer’s Gorilla, also known as the eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri), is a Critically Endangered subspecies found exclusively in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Primates in the DRC are primarily threatened by the mining of precious minerals at artisanal and industrial scale, poaching and pollution of soil and ground water.

Mining is the main driver of armed conflict in the region and stimulates human migration, wildlife trafficking, illegal logging for charcoal, colonization of forested areas, bushmeat hunting, and the construction of temporary roads in the forests. The extreme poverty in the region and the communities’ reliance on slash-and-burn agriculture are also drivers of great ape habitat degradation and fragmentation.

All of this has led to a rapid population decline of Grauer’s gorilla from an estimated 16,900 individuals in the wild in the mid-1990s to fewer than 3,800 individuals today.

The Soul of Congo's Forests

These gorillas have a remarkable jet black coat, reminiscent of their mountain gorilla relatives, but with shorter hair on both the head and body. As male Grauer’s gorillas mature, their once-black coat gradually transforms into a distinguished shade of grey, leading to the iconic designation of “silverback.”

The silverback, referring to the mature male leader of the group, stands out not only due to his silver-colored fur but also because of his impressive size and strength. These gorillas are the largest subspecies among their kind, and their robust build adds to their imposing presence in the dense, mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In the lush greenery of their habitat, Grauer’s gorillas navigate with a sense of grace, showcasing both power and agility. Their expressive eyes and thoughtful demeanor contribute to the overall aura of intelligence and complex social structure that characterizes these critically endangered primates.

Peaceful Leadership

Eastern lowland gorillas exhibit highly social and peaceful behavior, forming groups that range in size from two to over 30 individuals. Typically, a group comprises a dominant silverback, multiple females, and their offspring. The silverback, characterized by strength and leadership, serves as the protective leader (referred to as the alpha male), safeguarding the group from potential threats. As young silverback males mature, they gradually depart from their natal group, aiming to attract females and establish their own group.

The knowledge of the social behavior, history, and ecology of eastern lowland gorillas remains somewhat limited, partly because of civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nevertheless, certain aspects of their social dynamics have been studied. For instance, gorillas form harems, occasionally including two fully grown males. Approximately one-third of gorilla groups in East Africa consist of two mature males.

Female gorillas undergo a gestation period of about 8½ months, giving birth to a single infant. The breastfeeding period lasts for approximately three years, during which infants remain with their mothers for three to four years. Female gorillas mature at around 8 years old, while males reach maturity at 12 years old.

Upon reaching maturity, both females and males typically leave their groups. Females often join another group or a lone silverback adult male, while males may temporarily stay together until they attract females and form their own groups. This group structure is believed to serve as a protective measure against predation.

East Africa's Ecological Jewel

Grauer’s gorillas, or eastern lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri), primarily inhabit the mountainous forests of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo within the broader region known as the Albertine Rift.

Recognized as a biodiversity hotspot, the Albertine Rift is home to an extraordinary array of plant and animal species, many of which are endemic. Its lush montane forests harbor critically endangered species like the Grauer’s gorilla, as well as other rare mammals, birds, and plants. The unique ecological conditions of the Albertine Rift contribute not only to the survival of numerous species but also play a vital role in maintaining regional and global biodiversity. The conservation of this ecologically rich area is paramount for the protection of its unique flora and fauna.

Giant Anteater

Vulnerable

Ecological balancer

With its distinctive appearance and habits, the anteater has been featured in pre-Columbian myths and folktales, as well as modern popular culture. Unfortunately, it is now classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Human-induced threats include collision with vehicles, attacks by dogs, and destruction of habitat. In grassland habitats it is particularly susceptible to fires as its coat can easily catch fire and it is too slow to escape. The giant anteater is commonly hunted in Bolivia, both as a trophy and food and its leathery hide is used to make horse-riding equipment in the Chaco.

Photo : Asociacion Armonia

The giant anteater can be identified by its large size, long, narrow muzzle, and long bushy tail. It has a total body length of 182 to 217 cm and weigh from 27 to 50 kg, making it the largest anteater. Its head is particularly elongated, even when compared to other anteaters. Its cylindrical snout takes up most of its head with eyes, ears and mouth being relatively small. It has poor eyesight and relies primarily on a powerful sense of smell which is at least 40 times that of a human.

The giant anteater has no teeth and is capable of only very limited jaw movement. It’s oral opening is just large enough for its very long, slender tongue to flick out, moving in and out around 160 times per minute as it eats. It feeds primarily on ants and termites, using its fore claws to dig them up and its long, sticky tongue to collect them. It tracks prey by their scent and after finding a nest, tears it open with its claws and inserts its long, sticky tongue to collect its prey (which includes eggs, larvae and adult insects). It attacks up to 200 nests in one day, for as long as a minute each, and consumes around 35,000 insects each day.

Though giant anteaters live in overlapping home ranges, they are mostly solitary except during aggressive interactions between males, when mating, and mother-offspring relationships. Female anteaters give birth to a single offspring once a year, and carry it on their backs until weaned.

The Giant Anteater is widespread geographically ranging from Honduras to Bolivia and northern Argentina, but there have been many records of population extirpation, especially in Central America (where it is considered the most threatened mammal) and the southern parts of its range. The dietary specificity, low reproductive rates, large body size, along with threats to habitat degradation in many parts of its range, have proved to be significant factors in its decline. The species can live in both tropical rainforests and arid shrublands, provided enough prey is present to sustain it. In open habitats such as savanna in South America the abundance of native colonial insects, such as termites, provide its main food source.

The giant anteater is not only captivating but, above all, it plays a crucial role in maintaining the health and balance of ecosystems. Recognized as an insectivorous marvel, this species helps control ant and termite populations, contributing to pest regulation and the overall ecological equilibrium. Given its extensive distribution range in South America, multiple projects led by the International Conservation Fund (ICF) are actively working to preserve its habitat.

Blue-throated macaw

Ara glaucogularis

The Blue-throated Macaw (Ara glaucogularis), a magnificent bird adorned in turquoise and yellow plumage, stands at the brink of extinction with a precarious wild population of fewer than 300 individuals. Classified as Critically Endangered, this species faces a perilous future, primarily confined to the Beni Savanna of Bolivia.

A Tapestry of Turquoise and Yellow

Measuring approximately 85 cm (33 in) in length, the Blue-throated Macaw boasts a wingspan of around 90 cm. Weighing between 900 g and 1,100 g, these birds exhibit minimal sexual dimorphism, with males slightly larger than females. The upperparts shimmer in turquoise-blue, contrasting with a bright yellow underbelly and a pale blue vent. A distinctive facial patch, adorned with blue feather-lines and surrounded by bare pink skin, sets the blue-throated macaw apart. Notably, a sparsely feathered patch near the base of the bill, featuring unique horizontal blue stripes, serves as an individual identifier for each macaw.

Navigating Challenges

Typically forming monogamous pairs, these birds exhibit some flexibility with occasional small groups and, notably, larger roosting congregations. While their primary mode of locomotion is flight, they display versatility by climbing trees, maneuvering along branches, and walking on the ground. Active during daylight hours, Blue-throated Macaws communicate predominantly through sound, emitting loud alarming calls when sensing danger, and utilizing quieter caws for inter-species communication. Nesting in cavities of palm trees, especially the preferred Attalea phalerata, these birds demonstrate adaptability by utilizing dead palms, hollowed out by large grubs, as their preferred nesting sites. However, the challenge of deforestation looms large, as the Blue-throated Macaw contends for nesting sites with various other species. The decline in suitable nest trees underscores the urgent need to address deforestation issues, a critical aspect of ensuring the continued survival of this endangered species in its natural habitat.

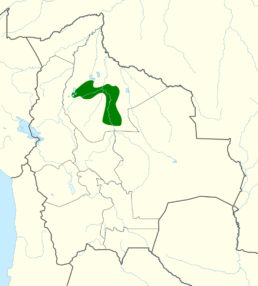

Pockets of Beauty in the Beni Savanna

The Blue-throated Macaw finds its sanctuary in the Llano de Moxos of the Beni Department in Bolivia, preferring the unique habitat of palm-dotted “Islas” (islands) on the level plains rather than traditional forests. This rare species is divided into two sub-populations, one to the northwest and the other to the south of Trinidad, the capital city of Beni. The landscape they inhabit is a complex mosaic of grasslands, marshes, forest islands, and riverside corridors of forests. Ranging between elevations of 200 and 300 m, the Blue-throated Macaw’s existence is intricately tied to this delicate and diverse ecosystem, making conservation of its habitat a critical component of preserving this species for future generations.

The Barba Azul Reserve

The Barba Azul Reserve serves as a crucial non-breeding habitat, hosting a significant portion of the remaining population, with a count of up to 155 birds recorded in 2017. The challenges this species encounters include historical factors such as nesting competition, avian predation, and a restricted native range, compounded by contemporary threats like hunting, trapping, tree cutting, invasive species, diseases, and fire control methods. Strict trading prohibitions aim to protect this species, but urgent conservation efforts are vital to ensure the blue-throated macaw’s continued existence in the wild. In a commitment to protect and bolster the population of the Critically Endangered Blue-throated Macaw and other species within the Beni Savanna ecosystem, the focus is on implementing conservation measures at the Barba Azul Nature Reserve. By addressing threats like habitat loss and deforestation, we strive to ensure the long-term survival of this magnificent species. Armonía’s dedication to the conservation of the Beni Savanna ecosystem remains steadfast, driven by the urgency to protect its biodiversity and sustain a harmonious environment for the future.