Many conservation initiatives start by protecting a rare species at risk of extinction (e.g. the Harlequin Toads in Santa Marta, Colombia or the Blue-throated Macaw in Bolivia). To protect the species in the short-term, this might mean setting up a new conservation reserve, restoring habitat, or removing a specific threat like deforestation or hunting. This can arrest the loss of individuals that would lead to extinction of the species, but it usually doesn’t stop the longer-term problems which caused the decline of a species (s) in the first place.

Photo: The endangered Harlequin Toad from Santa Marta Colombia

The Need for Corridors

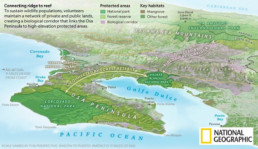

To protect the species in the longer-term, it is essential to protect the habitat on which the species depends, and to protect the habitat, at a larger scale, we must also protect the ecosystems that sustain the habitats. The habitat found within an ecosystem is not uniform and can vary considerably depending on topography, climate, disturbance events and a variety of other factors. Overtime, habitats can change in response to the ebbs and flows of ecological conditions. To protect the ecosystems, there needs to be strong connectivity between natural areas individuals and species to respond to changes in conditions affecting their habitat. In order to assist the adaptation of plant and animal life to the ongoing warming of our planet, conservation organizations need to prioritize tactics facilitating their migration towards higher elevations or cooler latitudes. Establishing protected biological corridors that connect lowlands to undisturbed areas within mountain ranges offers a method to reduce the risk of extinction for certain species.

Photo: This Spectacled Bear in Peru, needs a large area of habitat in order to forage for food to survive. In order for the species to survive, there must be a large connected area of habitat to maintain a population.

The Threat of Habitat Fragmentation

Global economic growth since WWII has lead to unprecedented levels of habitat degradation around the world. The maps below show the devastating loss of more than 98% of forests in Western Ecuador since World War II.

Map: Redrawn from Wilson, E.O. 1992. The Diversity of Life / C.H. Dodson and A.H. Gentry 1991. Biological Extinction in Western Ecuador. Ann. Missouri. Bot. Gard. 78: 273-295.

Connectivity is Essential for Survival

There are two main issues affecting the connectivity of an ecosystem that are closely related: patch size and degree of fragmentation. Patch area strongly influences the species richness of and diversity – the larger the patch, the greater the variety of habitat types which allows more species and greater diversity of species. When a large area becomes fragmented the habitats become isolated and no longer function the way they used to. The more fragmented a landscape becomes the more difficult it is for living organisms to reproduce, migrate, disperse, meet others of their own kind and have the genetic exchange needed to sustain their populations. Some species can persist in small patches, but if they are isolated from other patches, the species will eventually become extinct.

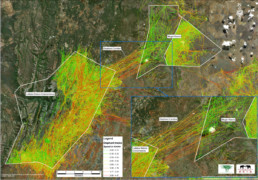

Map showing the movement of elephants between regions in their search for food. Green lines show elephant movements at a relaxed pace and red lines in a hurry. The majority of red lines occur outside of protected areas demonstrating the stress the animals are under in these regions because there is no habitat. Map courtesy of Mukutan Conservancy (aka Laikipia Nature Conservancy) and Mugie Ranch.

Reconnecting Ecosystems

Generally, protecting ecosystems means that large areas of natural habitat must be protected – not just any habitat – but blocks of habitat which maintain connectivity between patches of habitat. With the extensive fragmentation of ecosystems by human activities around the world, conservationists have developed the concept of creating “corridors” to protect the ecological functionality of existing ecosystems or to re-establish connections between fragmented patches

to report ecosystem function.

Photo: Shawn Carey

Corridors: A Conservation Solution

Corridors are typically defined as routes or zones that allow the unrestricted movement of living organisms between regions where they occur. The characteristics of a corridor will vary depending on the types of habitat and the species that live there, but to succeed, corridors must allow the movement of individuals and populations in space and time such that they can propagate, have sufficient genetic exchange between local populations, and be able to move in

response to changes in habitat over time (i.e. over multiple generations).

The El Oro Parakeets is a highly endangered bird found only in and near to Jocotoco’s Buenaventura Reserve. The species has been impacted by forest fragmentation and degradation, particularly by the loss of older trees in which they can nest. While the forests recover, Jocotoco has established a nest box program to provide nesting sites. This has seen an increase an increase in the population over 25% in just six years. Photo courtesy Jocotoco Foundation response to changes in habitat over time (i.e. over multiple generations).

El Oro Parakeets, Photo: Leovigildo Cabrera

When habitat loss happens in regions of the world with many range-restricted species, these species are particularly vulnerable to extinction because they have nowhere else to go. Ecological corridors have become an important organising concept for restoring connectivity and ecological function of ecosystems. Connectivity improves the capacity of living organisms to move in space and time and is an important aspect of ecosystem resilience. One of the earliest and largest conservation corridors was the Yukon to Yellowstone Corridor (Y2Y) established in 1993 to address the needs of species like Grizzly Bear, Wolf, Caribou and Caribou that require large ranges to maintain functional populations, harmonizing the needs of

nature with those of human communities.

Map by the Jocotoco Foundation showing the development of a corridor concept for its Buenaventura Reserve in western Ecuador. The green areas are existing patches of forest and the dots show the locations of two endangered bird species (less than 1000 individuals) whose habitats have been highly degraded and fragmented. The corridor planning seeks to reconnect existing habitat patches to allow an exchange between remnant populations.

As habitat fragmentation has accelerated over the last century, the ability of species to follow their normal ebbs and flows (migrations, dispersals, or to move in response to changes in their habitats) has been reduced. While most ecological fragmentation and degradation is being caused by human activities, there are many natural disturbances that can affect ecosystems on a large scale including fire, storm events, disease, drought, flooding, etc. In all cases, if too much habitat has been lost, these events can rapidly cause the extinctions of species.

Photo: yty.net