A Critical Discovery Reveals Hope for Vietnam’s Endangered Primates

Recent field surveys in central Vietnam have confirmed that some of the country’s most threatened primates are still surviving in the wild — and in places where their presence had never before been officially documented.

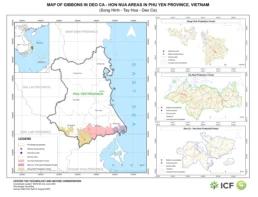

Within the contiguous forest complex of Deo Ca – Tay Hoa – Song Hinh, researchers confirmed six groups of Endangered Red-cheeked gibbons (Nomascus gabriellae), representing at least 15 individuals, and made a first-ever confirmed discovery of a group of Black-shanked douc langurs (Pygathrix nigripes) in Song Hinh Protection Forest. This finding marks the northernmost recorded distribution of the species to date.

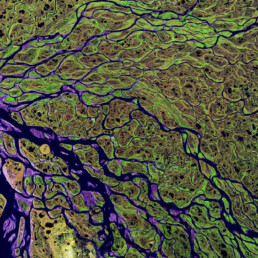

Covering more than 154 kilometers of systematic transect surveys, the study documented primate presence primarily through early-morning vocalizations, along with feeding and resting signs concentrated in streamside and riparian habitats. These forests form a connected landscape of up to 130,000 hectares, recognized as both a Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) and an Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE) site, underscoring their global ecological importance.

Despite this significance, the region faces persistent threats from hunting, habitat fragmentation, infrastructure development, and enforcement gaps — pressures that make these discoveries both hopeful and urgent.

Local Leadership at the Core: CTNC’s Role on the Ground

These results are the outcome of a project led by the Center for Technology and Nature Conservation (CTNC), a Vietnam-based grassroots NGO working directly with local authorities and communities to protect the country’s remaining wildlife and habitats.

Through a combination of scientific field surveys, technology-based monitoring, and community engagement, CTNC has demonstrated how locally led conservation can deliver concrete, measurable outcomes in complex and challenging landscapes.

The People Protecting the Forest: Rangers, Data, and Daily Patrols

A central pillar of the project focused on improving forest protection by equipping rangers with modern monitoring tools. Between April and August 2025, CTNC conducted three SMART training courses across Deo Ca Special-use Forest, Tay Hoa Protection Forest, and Song Hinh Protection Forest, training a total of 67 forest protection staff.

The Forest Has Neighbors — and They Matter

Recognizing that conservation cannot succeed without public understanding and support, CTNC also invested in outreach and education.

Environmental education programs reached nearly 1,000 students and teachers across three secondary schools, many of whom were unaware that globally threatened primates and turtles lived in the forests surrounding their communities. At the same time, public awareness campaigns using commune loudspeaker systems reached over 10,000 local residents, delivering repeated messages on wildlife protection laws, ecological importance, and legal consequences of illegal hunting and trade.

For the first time, patrol data were systematically recorded with GPS tracks, time stamps, and standardized threat reporting — allowing forest managers to identify enforcement hotspots and respond more effectively.

This effort moved quickly from training to real-world implementation. Following the handover of SMART-enabled mobile devices, patrol teams in Tay Hoa alone conducted:

21

patrols

46

patrol days

305.59

km covered

570

patrol hours logged

Why Local, Comprehensive Conservation Matters

Protecting Vietnam’s endangered primates is still possible — but only if these efforts are sustained and scaled. Support locally led conservation initiatives that combine science, enforcement, and community engagement to safeguard critical habitats before they are lost.

The achievements of this project — from species discoveries to improved enforcement and community engagement — were only possible because the work was led by people who understand the landscape, the species, the threats, and the social realities on the ground.

Photo by Tang A Pau

Effective conservation is not a single action or tool. It requires local expertise, scientific rigor, enforcement capacity, and community involvement, working together as a cohesive strategy. CTNC’s work in Phu Yen demonstrates what is possible when conservation is approached comprehensively and led by the right people in the field.

A Fragile Start: This Season’s Right Whale Calves

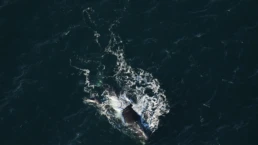

Calving season has begun — and already, two new North Atlantic right whale calves have been spotted!

Millipede (Catalog No. 3520) and her newborn were seen on December 3rd, about four nautical miles from the mouth of the St. Marys River on the Georgia–Florida line. The first calf of the season was born to a mother with the fittingly celebratory name Champagne.

Millipede seen with her third known calf. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, taken under NOAA permit #26919

These births matter.

With fewer than 400 right whales left on the planet, every calf is vital to the species’ survival.

Scientists estimate that for the population to recover, we need about 50 calves every year for many years in a row. Today, even a year with 20 calves is considered a “good” year. There is a fragile glimmer of progress. After sinking to an estimated low of 358 individuals in 2020, the population has shown slight improvement, with roughly 384 whales estimated in 2024. This doesn’t mean the species is safe — far from it — but it should motivate us to double down on conservation efforts.

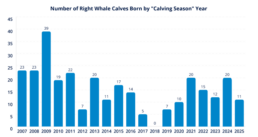

The number of North Atlantic right whale births. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Human-caused deaths remain the biggest obstacle to recovery.

Collisions and entanglements are the leading killers. Entanglements often cause deep injuries and chronic inflammation, leaving whales to weaken and die slowly from starvation.

Our partners at the Canadian Whale Institute are working on resolving entanglements on two fronts — rescuing entangled whales and collaborating with local fishers to prevent entanglements before they happen. Using the right gear, pulling nets during migration periods, and involving coastal communities directly in the solution are already making a difference.

A rescue mission by the Campobello Whale Rescue Team

A North Atlantic right whale with propeller scars. Credit: NOAA

If You’re on the Water: Slow Down

Vessel speed is critical. Slower boats mean fewer deadly collisions — and more time to avoid a whale altogether.

NOAA requires vessels 65 feet and longer to travel at 10 knots or less in seasonal management zones from Rhode Island to Florida. Smaller vessels aren’t legally bound by these rules, but NOAA strongly urges everyone to slow down.

Before heading out, check whale safety zones and recent sightings on the NOAA Right Whale Advisory System or the Whale Alert app. It’s a small action that can save a life.

The Right Whale to Save

The North Atlantic right whale earned its name because it was once the “right whale to kill” — slow, curious, and buoyant, making it the perfect target for whalers.

Today, we believe it’s the right whale to save. We are living at the last moment in history when their fate is still in our hands. After whaling pushed this species to the edge, Canadians and Americans now share the responsibility — and the privilege — of protecting this ocean giant.

Join us. Support the heroes at CWI and help keep this progress alive.

Champagne and her calf were sighted on December 5, 2025, Photo: Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute

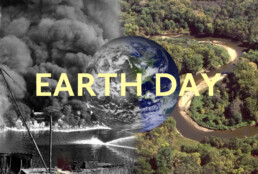

This Earth Day feels different

Dear Friends,

This Earth Day feels different.

Since the first Earth Day in 1970—which itself emerged from a wave of environmental disasters and rising public outrage—we’ve seen moments of progress, setbacks, and profound challenges. That first Earth Day was sparked by a series of shocking events: the Cuyahoga River catching fire in Ohio, the massive oil spill off Santa Barbara’s coast, and smog so thick in cities like Los Angeles that children couldn’t play outside. It was born from a crisis—just as we now find ourselves in another.

We are watching hard-won environmental protections of the past 50 years unravel. Political leadership that once championed science and sustainability is now accelerating destruction. And the climate crisis, once a distant warning, is here—flooding our cities, burning our forests, reshaping our world.

But perhaps the most unsettling part is this: it’s not just that we’re moving in the wrong direction. It’s that we’re losing the very mechanisms we need to find our way back. Trust in institutions. International cooperation. Shared truth.

And yet—despite it all—millions of people around the world are still fighting for the Earth.

In every region, on every continent, conservationists, scientists, Indigenous leaders, youth activists, and everyday citizens are protecting wild places, restoring broken ecosystems, and defending the future.

Their work is not always in the headlines. But it is unwavering. And it is full of hope.

At the International Conservation Fund, we draw strength from these stories. We believe in the power of resilience, in the quiet courage of those who refuse to give up, and in the deep, abiding truth that nature can recover—if we give it a chance.

So yes, this may be the darkest Earth Day since the first. But it does not have to stay that way.

Let us carry the torch through this dark age—together. Let us listen, learn, act, and give. Let us remind ourselves and each other that despair is not a strategy and that the future will be decided by what we choose to do now.

ICF funds cutting-edge conservation partners around the world, protecting some of the most endangered habitats and species against ever-increasing threats. Please take a moment to learn more about our Field Partners and consider making a donation to support their work.

This Earth Day, don’t turn away. Turn toward the work. Toward each other. Toward the Earth.

With resolve and hope,

International Conservation Fund

The U.S. Led the World in Conservation—We Can Do It Again

The United States has played a unique role in the history of conservation. At times, it has been seen as an obstacle to global environmental progress—resisting international climate agreements, rolling back protections, and allowing denial to stall urgent action. But just as often, it has led the world—pioneering national parks, shaping international treaties, and inspiring movements through art, activism, and philanthropy. American scientists have uncovered the dangers of pollution, American leaders have signed groundbreaking environmental laws, American philanthropists have funded conservation on a massive scale, and American citizens have marched, organized, and demanded change. Today, as we face new environmental challenges, it’s crucial to step back and see the bigger picture. History shows us that progress is possible—and that when Americans rise to the occasion, we don’t just change our country. We change the world.

“The battle for conservation must go on endlessly. It is part of the universal warfare between right and wrong.” - John Muir

John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, two pioneers of American conservation, united in their vision to protect the natural beauty of the United States. (Credit: National Park Service)

The story of American conservation began with a bold idea: that nature, in all its beauty and grandeur, should belong to the people and be preserved for future generations. In 1872, the United States created Yellowstone National Park, the first of its kind in the world. This revolutionary act not only safeguarded a vast and breathtaking landscape but also set a precedent for conservation efforts across the globe. It was the first step in a long journey—one that would lead to the establishment of national parks, wildlife refuges, and environmental protections that continue to shape the world today.

From the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 to the passage of the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts in the 1970s, the U.S. has been at the forefront of efforts to protect the environment. The fight to ban DDT, the success of the Montreal Protocol, and the global impact of Earth Day—first organized in the U.S. in 1970—are just a few milestones in a long history of environmental progress.

“We have fallen heirs to the most glorious heritage a people ever received, and each one must do his part if we wish to show that the nation is worthy of its good fortune.” - Theodore Roosevelt

"Clean air, clean water, open spaces - these should once again be the birthright of every American." - Richard M. Nixon

Yet, no single list could ever capture the full scope of these achievements, nor the countless individuals who have dedicated their lives to conservation. Scientists, activists, philanthropists, and everyday citizens—in the U.S. and around the world—have worked tirelessly to protect the planet, often against great odds. Their efforts, whether in the halls of government, the depths of the oceans, or the pages of a book, have shaped the way we understand and care for our natural world.

Today, our partners at Jocotoco are not only protecting existing wilderness but also achieving an ambitious goal: rewilding Floreana Island in the Galápagos. By restoring ecosystems and reversing 200 years of ecological damage, they are setting a powerful example of what conservation can accomplish.

Environmentalism is not bound by time or borders. The passion of one generation inspires the next, and the actions of individuals ripple outward, creating a force for change that stretches across continents. Just as Rachel Carson’s warnings about pesticides ignited a movement, just as American conservationists helped establish the first global environmental treaties, the work we do today will inspire those who come after us. The story of conservation is still being written—and we each have a role to play.

The pursuit of science and truth can create a false sense of optimism—the belief that because truth reflects reality, it will inevitably prevail. And in one sense, it will: climate change is not a matter of debate, but a fact that is already reshaping our world. But will truth prevail where it matters most—in the consciousness of people, in our institutions, in the decisions that shape the future? The fight against climate change has made it painfully clear that we cannot take this for granted.

Unprecedented wildfires tear through forests and communities. Drought strikes even the rainforests. Coral bleaching ravages fragile marine ecosystems. Species are vanishing at catastrophic rates, and entire ecosystems are being pushed to the brink of collapse. This is the painful and undeniable reality—yet half of Americans refuse to accept the science. They continue to vote for leaders who shape domestic and international policies based on denial and misinformation. Despite the tireless efforts of scientists, activists, journalists, and policymakers, climate denial remains deeply entrenched.

Environmental protection is, without question, one of the most urgent challenges facing humanity—but we are not confronting it as a united front. Instead, the fight for the planet is waged in countless, scattered battles: scientists racing to document vanishing species, activists working to reclaim their institutions, Indigenous communities defending their land and culture against destruction.

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.” - Rachel Carson

Kayapo Celebration (Credit: Takakrua Kayapo)

On the frontlines of deforestation, the Kayapo people are safeguarding over 9 million hectares of rainforest. Their decades-long success stands as proof of the power of Indigenous knowledge, sustained philanthropy, and strong institutions. Despite political challenges and external pressures, the Kayapó have remained resilient—demonstrating that sustained support and institution-building are key to long-term conservation.

Even in times of division and isolationism, there is strength in connection. Across borders and disciplines, across movements and generations, we are part of a vast and interwoven network of people fighting for nature. In this web of defenders—scientists, advocates, land stewards, and educators—our power lies in learning from one another, supporting each other, and standing together. The work ahead will not be easy, but it is shared. And together, we can push forward.

Despite the challenges we face, there is good news: the network of individuals fighting for conservation is real, and it is stronger than ever. Across the globe, people have been building knowledge, protecting ecosystems, and defending biodiversity. Indigenous communities have not only safeguarded their lands but have also built institutions to ensure their voices are heard. Scientists and conservationists have spent decades exchanging knowledge, expanding our understanding of species and ecosystems, and developing solutions that will guide us forward.

In this era of political uncertainty and geopolitical instability, we must do everything in our power to maintain and strengthen these connections. Conservation has always been a collective effort, and the institutions that support it—whether scientific, governmental, or grassroots—are more important than ever. The International Conservation Fund is privileged to work alongside incredible partners around the world, many of whom face great challenges and uncertainty. But we remain committed to this work, to them, and to building upon the hard-won achievements of those who came before us.

There are thousands of conservation projects around the world that go unnoticed and millions of individuals holding invaluable knowledge and skills—each representing a piece of a puzzle we must solve together. The pieces fit; we just need to connect them, strengthen them, and ensure they endure. Take a moment to explore the partners that ICF supports. Learn about their projects, amplify their work, and contribute to conservation efforts that will leave a lasting impact—one that ripples across generations and ecosystems.

The future of conservation is still being written, and it is up to us to ensure that this legacy not only endures—but grows.

Fundación Atelopus with the Arhuaco Indigenous People, working together to protect biodiversity. (Credit: Fundación Atelopus)

Barbara Zimmerman, side by side with the Kayapo guardians, safeguarding the Amazon. (Credit: Martin Schoeller)

Scott Hecker together with our Indigenous Wounaan partners in Panama.

Sweet fishing cat kittens caught on video

Fishing Kittens Spotted!

These adorable Fishing Cat kittens were spotted on a camera trap deep in the Cambodian mangrove forests—a sign of life and resilience in a challenging habitat. These vulnerable cats face threats like poaching, but thanks to the dedication of our partners at Fishing Cat Ecological Enterprise (FCEE), their future looks brighter.

Camera traps not only let us celebrate moments like this but also help us detect and combat poaching to protect these incredible animals. Together, we can safeguard their home and ensure they thrive! Join us at the International Conservation Fund for updates on the amazing work of our field partners!

Our partners, including the Fishing Cats Ecological Enterprise (FCEE), the Kayapo, and Osa Conservation, are using camera traps to monitor and protect wildlife. These tools are efficient, cost-effective, and non-invasive, providing invaluable insights while preserving natural habitats.

Conservation under the wings of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper

Umbrella species: The Spoon-billed Sandpiper

Protection of Wetlands Across Asia

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper, a vital umbrella species, migrates along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), one of the most critical and diverse migratory routes worldwide. This flyway spans over 8,000 kilometers, connecting breeding grounds in northeast Russia with key wintering sites across Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, China, and other regions.

As an umbrella species, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper’s conservation indirectly protects numerous other species within these ecosystems. The EAAF hosts many endangered bird species, such as Great Knot and the Black-faced Spoonbill. Conservation actions, including wetland protection and regulations against hunting, are critical for maintaining this route and support the survival of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and other species reliant on these shared habitats across Asia.

33 globally threatened and near threatened species and almost half a million waterbirds benefit from the Spoon-billed Sandpiper focused conservation efforts.

Spoon-billed Sandpiper breeding ground in Chukotka, Russia

The coastal tundra breeding grounds in Chukotka, where the Spoon-billed Sandpiper nests, host a unique array of Arctic bird species that thrive in the same specialized habitats.

Removing Mist Nets: One Action, Many Species Protected

Mist nets, often used illegally for bird trapping, pose a significant threat to the critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper, especially in key wintering areas and stopover sites along its migratory route. These nets not only capture Spoon-billed Sandpipers but also entangle numerous other migratory birds, including endangered species like the Black-faced Spoonbill, Nordmann’s Greenshank, and the Far Eastern Curlew. By removing mist nets, our partners help reduce accidental capture and mortality, which is especially crucial for species with small, vulnerable populations.

International Cooperation Under the Umbrella of the Spoony

Protecting the Spoon-billed Sandpiper has sparked unprecedented international collaboration across Asia, linking conservation organizations, governments, and communities in a shared mission. This effort is building a strong regional network of environmental action, with countries working together to safeguard crucial wetland habitats, regulate hunting practices, and share research and resources. The sandpiper’s conservation is not only a strategy for its survival but a powerful catalyst for strengthening biodiversity protection and environmental cooperation across borders in Asia.

The many organizations working to save the Spoon-billed Sandpiper

ArcCona Consulting

Bangladesh Spoon-billed Sandpiper Conservation Project

Bangladesh Forest Department

Beijing Forestry University

Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Club

Birds Korea

Birds Russia

BirdLife International

BirdLife International in Indochina and University of Saigon

Bombay Natural History Society

BRC (Guangxi Biodiversity Research and Conservation Association)

BTO

Chester Zoo

Convention on Migratory Species

Conservation Ecology Program

School of Bioresources and Technology

King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT)

Department of National Parks

Wildlife and Plant Conservation of Thailand (DNP)

Duotan Wetland Research Institute (Hainan)

Fujian Birdwatching Society

German, Scandinavian and UK Spoon-billed Sandpiper Support Groups

Heritage Expeditions

Hong Kong Bird Watching Society

International Conservation Fund

International Conservation Fund of Canada

Liuzhou Birdwatching Society (Guangxi Province)

Mangrove Conservation Foundation

Moscow Zoo

Nanjing Normal University

Nature Conservation Society-Myanmar

New Zealand Department of Conservation

RSPB

SCOPE Foundation

SBS in China

University of Cambridge

Wader Quest

Wild Bird Society of Japan

WWT

Zhejiang Birdwatching Society

Zhanjiang Birdwatching Society

Zhiyu Art Museum (Guangxi Province).

Shorebird Stories

Conservation under the wings of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper

October 29, 2024

Conservation actions supporting the Spoon-billed Sandpiper in the wetland areas of East Asia benefit many other endangered species across Asia.

The Spoony of Peace

October 20, 2024

Much like the symbolic dove carrying an olive branch, the spoon-billed sandpiper transcends borders and politics, uniting governments, conservationists, and local communities in the shared mission of preventing its extinction.

The Spoony of Peace

Can Environmental Cooperation Survive in a Divided World?

International relations and cooperation between superpowers like the U.S., Russia, and China are at historic lows. Most of what we hear is about rivalry, tension, and military escalation. The prospects of a new Iron Curtain dividing the world are realistic, and only history will tell us if we have already crossed that point. However, even during the height of the Cold War, scientific and environmental cooperation between the USSR and the U.S. existed and served as a source of hope for peace and prosperity for humankind. Under the 1972 Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Environmental Protection, the U.S. and the USSR worked together on wildlife conservation efforts, focusing on preserving biodiversity and protecting endangered species in their respective territories. Efforts to protect the Siberian tiger and the American bison were at the heart of that collaboration. American and Soviet scientists researched data and exchanged anti-poaching strategies; they also collaborated to understand the ecology, behavior, and population dynamics of the Siberian tiger. Can we still do this today?

A Siberian tiger photographed by a camera trap. Taken by Svetlana Sutyrina

A “spoonie” on the breeding grounds in Chukotka, Siberia, June 2015. photo by Mads Syndergaard

Spoony of peace

Saving the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Across Political Divides

In today’s context, it’s hard to find a more hopeful example of international collaboration than the effort to save the spoon-billed sandpiper. This small, critically endangered shorebird migrates across some of the most politically tense regions in the world—China, Russia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, North Korea, and South Korea. Much like the symbolic dove carrying an olive branch, the spoon-billed sandpiper transcends borders and politics, uniting governments, conservationists, and local communities in the shared mission of preventing its extinction.

A Common Goal

The spoonie’s decline was rapid, primarily due to habitat loss from land reclamation and hunting. Today, with only around 100 breeding pairs left, its survival depends on conservation efforts spanning over 8,000 kilometers—from its breeding grounds in Russia’s Chukotka region to its wintering grounds in South and Southeast Asia. These efforts, involving multiple countries, share a common goal: halting the species' decline by 50% by 2025.

A Global Strategy

Ambitious goals require even more ambitious actions, and that is precisely what the multidisciplinary team of conservation scientists, coordinators, and strategists has been doing. Russian expedition teams, UK breeding programs, Chinese satellite tracking, and monitoring at key staging and wintering sites are all working together toward the common mission of creating a future for the spoon-billed sandpiper and millions of other migratory shorebirds of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway.

Conservation in Action

The scale, complexity, and urgency of the situation require diverse and immediate actions. Spoon-billed sandpiper migration is being tracked with satellite tags. A captive population has been established as a safeguard against extinction. Key sites in Myanmar, China and the South Korea have received protected status including some World Heritage Sites on the Yellow Seas of the latter two countries, covering an area of over 430,000 ha.

Spoon-billed Sandpiper hatchlings, photo: Pavel Tomkovich

Other significant efforts to protect the Spoon-billed Sandpiper include:

> Headstarting

A headstarting program for spoon-billed sandpipers has been underway since 2012, involving specialists collecting eggs from incubating birds in the wild, hatching and hand-raising the chicks in captivity to fledging age, and releasing the birds back into the wild. Headstarting efforts have released over 180 birds. This intervention protects the eggs and chicks during the particularly vulnerable incubation and rearing phases. Unfortunately, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict has caused a pause in spoonie headstarting work. While headstarting activity is necessarily paused, the team has begun preparing for a potential return to full operations, hopefully in 2025, despite the existing challenges.

> Stopping Hunting

The EAAFP Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force is working with villagers in Myanmar and Bangladesh to ease the pressure of trapping. Good progress is being made to stop bird trapping on the spoon-billed sandpipers’ non-breeding grounds. Bird trappers sign agreements to cease hunting in return for small grants to buy fishing equipment. The East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force estimates that as many as 80-90% of hunters in the Bay of Martaban, Myanmar (the most important wintering site in the world for the spoon-billed sandpiper), have now signed agreements to stop hunting and surrendered their trapping equipment. Advocacy work is raising the profile of the critically important intertidal wetlands in the Yellow Sea. Awareness-raising activities are introducing this incredible bird to children in the flyway. Annual surveys of breeding sites in Chukotka have been undertaken, with over 400 birds color-marked since 2012. A new breeding site, “Okeanskoe,” has also been discovered!

Net removal in South China

Are we up to the task?

The story of the spoon-billed sandpiper reminds us that conservation is a global challenge that requires collective action. No single country can save a migratory bird like the spoonie on its own—preservation depends on seamless cooperation across borders, cultures, and political ideologies. This species knows no boundaries, and its survival requires the same boundaryless approach from humanity.

In a world facing immense challenges like biodiversity loss and climate change, the spoon-billed sandpiper stands as a poignant symbol of our shared humanity. Its plight illustrates that we are all interconnected; the fate of one species is intricately tied to the well-being of our planet and, ultimately, to our own survival. The collaborative efforts to save the spoonie remind us that when we unite for a common purpose, we can achieve great things—overcoming political divisions, cultural differences, and economic disparities. In essence, the conservation of the spoon-billed sandpiper is not just about saving a bird; it is about fostering a sense of global community and shared responsibility. By working together, we can confront the pressing environmental challenges of our time, ensuring that future generations inherit a thriving planet rich in biodiversity. The collective action we take today, motivated by the fate of this remarkable bird, may well determine the course of humanity’s relationship with

nature.

Shorebird Stories

Conservation under the wings of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper

October 29, 2024

Conservation actions supporting the Spoon-billed Sandpiper in the wetland areas of East Asia benefit many other endangered species across Asia.

The Spoony of Peace

October 20, 2024

Much like the symbolic dove carrying an olive branch, the spoon-billed sandpiper transcends borders and politics, uniting governments, conservationists, and local communities in the shared mission of preventing its extinction.

Join the international efforts to save the Spoony by supporting our field partners in Myanmar, Bangladesh, China, and Thailand.

Rewilding the Galapagos: Bringing Back Lost Species

Rewilding the Galapagos: Jocotoco Is Bringing Back Lost Species

Galapagos. Close your eyes for just a moment. What images does the name conjure in your mind? Primordial forces: volcanoes, evolution. Bizarre creatures, blue waters teeming with life. Nature—untamed, isolated, and unspoiled by humans.

For millions of years, this is how the islands looked. Just as volcanic activity continuously shaped them, life on the islands took its own course, and evolution created a completely unique ecosystem, as it often does on remote islands. This remained the case for millennia until the first humans set foot on the islands in the 16th century. Sporadic visits by pirates and whalers were enough to take a terrible toll on the ecosystem. As with most islands, the Galapagos suffer from invasive predators introduced both deliberately (goats and other domesticated animals) and unintentionally (rats and mice). These invasives have decimated local populations of birds and other wildlife. Hunting by whalers and pirates over the centuries disrupted the ecosystem’s balance and wiped out many endemic species.

Pink Land Iguana, Marlon del Águila

Today, our partner Jocotoco has an ambitious plan to restore the beauty and diversity of the Galapagos Islands for future generations, harnessing the ecological superpowers of a tortoise species once thought extinct. The rewilding of the Galapagos island of Floreana, will make it the largest tropical island ever to be rewilded!

First Step: Removing Invasive Species

The first step was removing invasive predators from the island, which was accomplished toward the end of last year. This was no easy task. Eradicating invasive species like rats, mice, and feral cats on a 173 km² island is a monumental challenge, but it was successfully completed thanks to the tireless efforts of Jocotoco, the Galapagos National Park, and many local and international partners.

“Invasive species are destroying our island. They devour crops and are pushing our seabird populations to the brink of extinction. We catch less fish every year. By removing invasive species, we have the opportunity to restore both the land and the sea and provide more ecotourism opportunities for the first time on an inhabited island in the archipelago. Our livelihoods, our health, and the next generation’s future depend on it.” —Max Freire, Floreana Island native and fisherman

“Every action has a reaction, and it has been well-established that removing invasive species from islands paves the way for ecosystem recovery.” —Chad Hanson, Deputy Vice President of Conservation at Island Conservation (source)

Park rangers working on manual bait dispersion during the invasive species eradication phase. – Photo by Joshua Vela

Next Step: Reintroducing Lost Species

“Rewilding is a key concept in this endeavor, as it involves returning these species to their natural environment—a crucial step toward revitalizing a healthy and balanced ecosystem.” – Jocotoco website

With the invaders gone after 150 years, it’s time for the most exciting part of the rewilding process: bringing back the lost species! Our partners at Jocotoco aim to reintroduce 12 of the 13 locally extinct species to their natural habitat, including the Floreana Giant Tortoise, Floreana Mockingbird, Little Vermilion Flycatcher, Galapagos Rail, Lava Gull, Galapagos Hawk, Vegetarian Finch, Gray Warbler Finch, Sharp-beaked Ground Finch, Large Ground Finch, Barn Owl, and the Floreana Racer Snake.

Earlier this year, more than 500 Darwin’s Finches were released on Floreana Island. The birds are successfully returning to their natural territories! Though small, their presence has a large impact: they pollinate, disperse seeds, and control insect populations.

“We’ve planned this moment for so many years; it’s surreal to experience it. The release of these finches marks a monumental moment for the future of Floreana.” – Paula Castaño, from Island Conservation (source)

Large Ground Finch by Jocotoco

The Ecological Engineers Are Returning

The Floreana Tortoise went extinct over 150 years ago, likely during the 1840s or 1850s. By the time Charles Darwin famously visited the Galápagos Islands in 1835, decades of overharvesting had already brought the population to the brink of extinction. Darwin noted that only about 20 years’ worth of harvestable tortoises remained. The species finally disappeared around 1850.

Fortunately, in 2012, several hybrids between the extinct Floreana Tortoise and Chelonoidis becki, another subspecies, were discovered near Wolf Volcano on Isabela Island. These were likely descendants of Floreana tortoises transported there in the early 19th century. In 2017, a breeding program was launched to revive the Floreana subspecies. By 2023, the program had successfully produced around 400 offspring, offering a unique opportunity to repopulate Floreana Island with tortoises that closely resemble the genetic makeup of the original Floreana Giant Tortoise.

Photo by Diego Bermeo, DPNG

Galápagos Tortoise, Josgua Vela

The return of the tortoise to Floreana will be more than a symbolic victory. The tortoise will serve as an environmental engineer, transforming the island to benefit other endangered species. Not only do they disperse seeds and move soil, but they also “terraform” the habitat by consuming large amounts of lower vegetation, opening up the understory for foraging by species like the endangered Floreana Mockingbird and Little Vermillion Flycatcher. Jocotoco’s work in the Galapagos represents a unique conservation opportunity with lasting consequences for Floreana and the preservation of Earth’s biological treasures.

“This restoration project yet again demonstrates the importance of coordinated efforts between institutions and organizations dedicated to conserving the Galapagos Islands. Large-scale projects like this can only achieve positive results when all conservation stakeholders pool their knowledge, efforts, and collective experience.” —Rakan Zahawi, Executive Director of the Charles Darwin Foundation (source)

Time to make a real impact

This work might be expensive and challenging, but it’s worthwhile! The 160 people who live on Floreana have already seen their crop yields increase dramatically with no rats or mice around. The return of tortoises and birds will bring increased tourism revenue, a win-win for both people and wildlife.

At ICF, we’re thrilled to support Jocotoco’s work in Floreana, and we’re eager to invite you to join us. Support Jocotoco’s work in Floreana through ICF, and let us know if you’re interested in joining an ICF trip to the Galapagos in 2025! Jocotoco’s tour company, Jocotours, offers a unique opportunity to see this incredible work firsthand.

Juan Pablo Mayorga (Jocotoco Foundation), coordinating work with Biosecurity Agents (ABG) Photo by Joshua Vela

Celebrating Earth Day from Ecuador! | April, 2024

Dear friends,

For Earth Day we highlight the work of the Jocotoco Foundation based in Ecuador.

Ecuador is a mega-diverse country with the highest biodiversity per area of any country. Many species in Ecuador are found only in very small areas (endemics). Tiny Ecuador is home to 16% of the world’s bird and 10% of the world’s amphibian species. Ecuador was the first country to give nature constitutional rights and it has protected close to 20% of its land and sea territory. In spite of these successes, the threats remain. For example, over 95% of forest has been lost in the lowlands of western Ecuador.

The Blue-throated Hillstar was only recently discovered and the world population is between 80-120 individuals. Photo: Murray Cooper

The population of many parrots is limited by the availability of nest cavities because so many trees have been cut down. A nest box program provides homes to these birds like this rare White-breasted Parakeet until the forest can regrow. Photo: Byron Puglia.

Jocotoco was established in 1998 to protect the many endangered and endemic species which are still not protected by Ecuador’s relatively extensive system of protected areas. In 25 years, Jocotoco has established 18 conservation reserves totalling over 40,000 ha.

The foundation’s first reserve was established to protect the Jocotoco Antpitta is south-eastern Ecuador – then a new species to science. The foundation flourished and initially focused on protecting endangered birds like the El Oro Parakeet, Ecuadorian Tapaculo, Pale-headed Brush Finch, Great Green Macaw, Black-breasted Puffleg and Andean Condors.

The Jocotoco Antpitta was discovered in 1998 in southern Ecuador. The population is thought to be around 500. Photo: Doug Wechsler

Jocotoco now protects over 10% of all the world’s bird species in just 0.00003% of the world’s land area.

Jocotoco quickly recognized that to protect endangered birds, they had to protect the habitats and ecosystems in which they lived. This meant working with many stakeholders, communities, and governments in order to protect larger areas. The results have been astonishing, showing how resilient nature can be if given a chance! In all its reserves, Jocotoco has seen a marked increase in rare species, especially in areas reforested to reconnect remaining old growth forest patches.

“I have watched and supported Jocotoco since they first were formed. It is inspiring to see how much land and critical habitat has been conserved in just 25 years and how well this has been supported by the communities and governments in Ecuador. Seeing these natural ecosystems recover so quickly with protection is a very hopeful message for Earth Day!”

Jerry Bertrand, Founding Board Member ICF

With habitat protection on conservation reserves, large mammals like these Mountain Tapirs have returned and are increasingly common. Photo: Jocotoco

Protecting the Lowland Chocó

ICF and its staff have been supporting Jocotoco’s major initiative to protect the Chocó Forest Ecosystem since 2016. With less than 2% of the original forest remaining in this species and endemic rich area, the situation is still critical. To date over 15,000 ha has been protected by Jocotoco and its partners and a connection has been established between Jocotoco’s reserve and Cotocachi-Cayapas, one of Ecuador’s largest national parks. While much more work remains to be done, the establishment of these protected areas is ensuring the long-term survival of healthy populations of Jaguars, Harpy Eagles, and Peccaries. The removal of hunting pressure has seen the return of shy species like the Great Curassow, and recently a Giant Anteater.

Click to view this video of a Giant Anteater at Jocotoco’s Canandé Reserve: one of the first records of this species west of the Andes in a very long time.

Photo: Humberto Castillo

Canandé Reserve becomes Ecuador’s Newest National Park

In November 2023, the Government of Ecuador included 2900 ha (about 25%) of Jocotoco’s Canande Reserve into the National Park System. The advantage is that this provides legal protection from all extractive uses – particularly mining. Jocotoco is working with the government and community groups to include the remaining areas. You can see Canande as Ecuador’s newest national park — # 78 on the attached map. This brings Ecuador’s National Park System coverage to almost 20% of the country.

Science Innovation in the Chocó

Effective conservation depends on having the best knowledge available. When Jocotoco started to work in the Chocó in 2000, almost nothing was known about the area and how complex it was. It was a very difficult region of the world to reach and get access to.

After much preliminary work, a coalition of German, Ecuadorian and other international researchers established a research program to explore and understand the Chocó. This led to the formation of the REASSEMBLY project led by Nico Blüthgen and Martin Schaefer – funded by the German Science Foundation.

In short, this is targeted research to understand how complex tropical forest ecosystems work and how ecosystems reassemble themselves after disturbance from forestry or agriculture. The GOOD NEWS is that almost everything can return within a human generation – nature is resilient if given a chance!

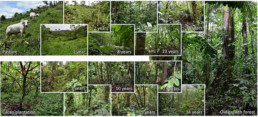

This photo montage shows some of the ecological conditions and age categories of forest being studied by researchers. Photo: REASSEMBLY.

Join us at Chautauqua!

Effective conservation depends on having the best knowledge available. When Jocotoco started to work in the Chocó in 2000, almost nothing was known about the area and how complex it was. It was a very difficult region of the world to reach and get access to.

After much preliminary work, a coalition of German, Ecuadorian and other international researchers established a research program to explore and understand the Chocó. This led to the formation of the REASSEMBLY project led by Nico Blüthgen and Martin Schaefer – funded by the German Science Foundation.

Join us at Chautauqua!

Thanks from all of us and happy spring!

David, Molly, Scott, Jerry, Meade, Wayne and Doug

ICF has a new website and fresh look for Spring! | Newsletter April 2024

At the International Conservation Fund we are also busily refreshing our look and our approach with the launch of a new website. We continue to fund important conservation work for our Canadian partner, but we are branching out to directly fund conservation projects as well. We at ICF, have organized our approach around four overarching themes: Saving Shorebirds; Working with Indigenous Peoples; Protecting Species, and Landscape-level Connectivity, emphasizing climate resiliency and mitigation and migratory corridors. Also new, we feature the work of our in-country field partners to emphasize their success as leaders in their regions who plan and implement community-led, long lasting conservation initiatives.

Take a tour and let us know what you think!

As always, your support makes this important mission possible. Spring is a nice time of year to pitch-in as we start a new year with new partners, and a renewed sense of hope!

Thanks from all of us and happy spring!

David, Molly, Scott, Jerry, Meade, Wayne and Doug